The Structure of Player Choices.

I’ve been designing board games as a hobby for a couple of years now. This is by far the most valuable thing I’ve learned.

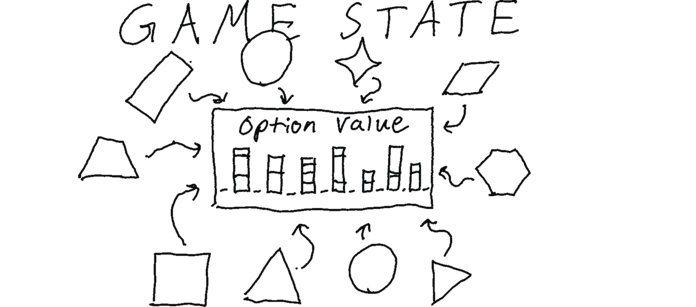

Player Options and Game State

When a player has to make a choice, the “best” option should depend on the state of the rest of the game.

In Sushi Go, players draft one sushi card from a hand of cards before passing the rest to the next player. There are nigiri cards that reward 3 points and sashami cards that reward 10 points once you’ve collected 3. If you have to choose between these cards, which is the better option? The answer is that it depends.

- How many sashami cards do you have?

- How many cards are left to draft?

- How many sashami cards have you seen so far?

- Are other people working on sashami cards?

- Are you working on other types of sushi?

In a vacuum, this choice is incredibly simple, but it becomes interesting once you include the complexity of the rest of the game.

The effect of this dynamic is that players have to observe and reason about the details of the game when making choices. This engagement is the core experience of most strategy games.

| Example Choice | Outside Factors | |

|---|---|---|

| Wingspan | Which birds to play? | Bonus cards, round end goals, food supply, egg supply, current tableau… |

| Pandemic | Treat the disease or trade cards? | Cards in hand, cubes on board, turns remaining, outbreaks remaining… |

| Cascadia | Which tile and animal to draft? | Completion of animal goals, size of biome, priority of other players, acorn supply… |

“Balance” is situational.

Most player options shouldn’t be inherently balanced or inherently unbalanced. Sushi Go would be less fun if all sushi cards rewarded flat points. Instead, options should be situationally unbalanced as a result of the game state.

Granted, you don’t want the best option to always be obvious, but as long as most choices have at least two similarly viable options available, players still have compelling choices to make. There are turns in Pandemic where a player simply must pick up some disease cubes to avoid a loss, but most turns are still agonizing.

Balance is statistical. You want any particular option to be the best choice a reasonable percentage of the time, but there’s a lot of wiggle room there. As long as a card has a trade off which gives it some common situation where it’s viable, that’s enough to justify it’s inclusion in the game. To me, overpowered means that an option is always the best choice and underpowered means it’s never the best choice.

Exceptions and caveats.

This may not apply to choices in games where the challenge isn’t decision making:

- dexterity games

- deduction games

- social deduction games

- bluffing or lying games

- real-time games

It may, however, apply to some elements of these games. Like how in The Search for Planet X the main challenge is deduction, where you’re always trying to figure out as much as you can, but you still have a choice of when to put down theories.

This also may not apply to games that are intended to only be played once or a few times. In Gloomhaven, event cards present a choice to the players for which the outcome is predetermined and unaffected by the rest of the game, but since you’re expected to only see these once, you don’t need that variability.

Not every choice needs nuance. After a battle in Eclipse, players draw victory point tokens from a bag which have a random value from 1 to 4. They can then choose a token to keep, but it’s obvious that they should pick the higher value. As long as a game has enough interesting choices to provide a challenge and keep players engaged, that’s good enough.

Player options are also not the same thing as components. I’ve been referring to cards a lot, but in For Sale, the best property cards are obvious and unchanging (they’re marked with their value). But you aren’t picking between cards in For Sale; you’re bidding on them. The choice is what to bid, so the cards themselves need not ever change in value.

And, of course, you can break this rule whenever you want. I haven’t played Vantage yet, but my understanding is that the outcome of successful actions never changes. This may make some options bad irrespective of the rest of the game, but that would serve a valid purpose: Vantage wants you to become familiar.